Material Languages: A Machine Dreams of African Print (2021)

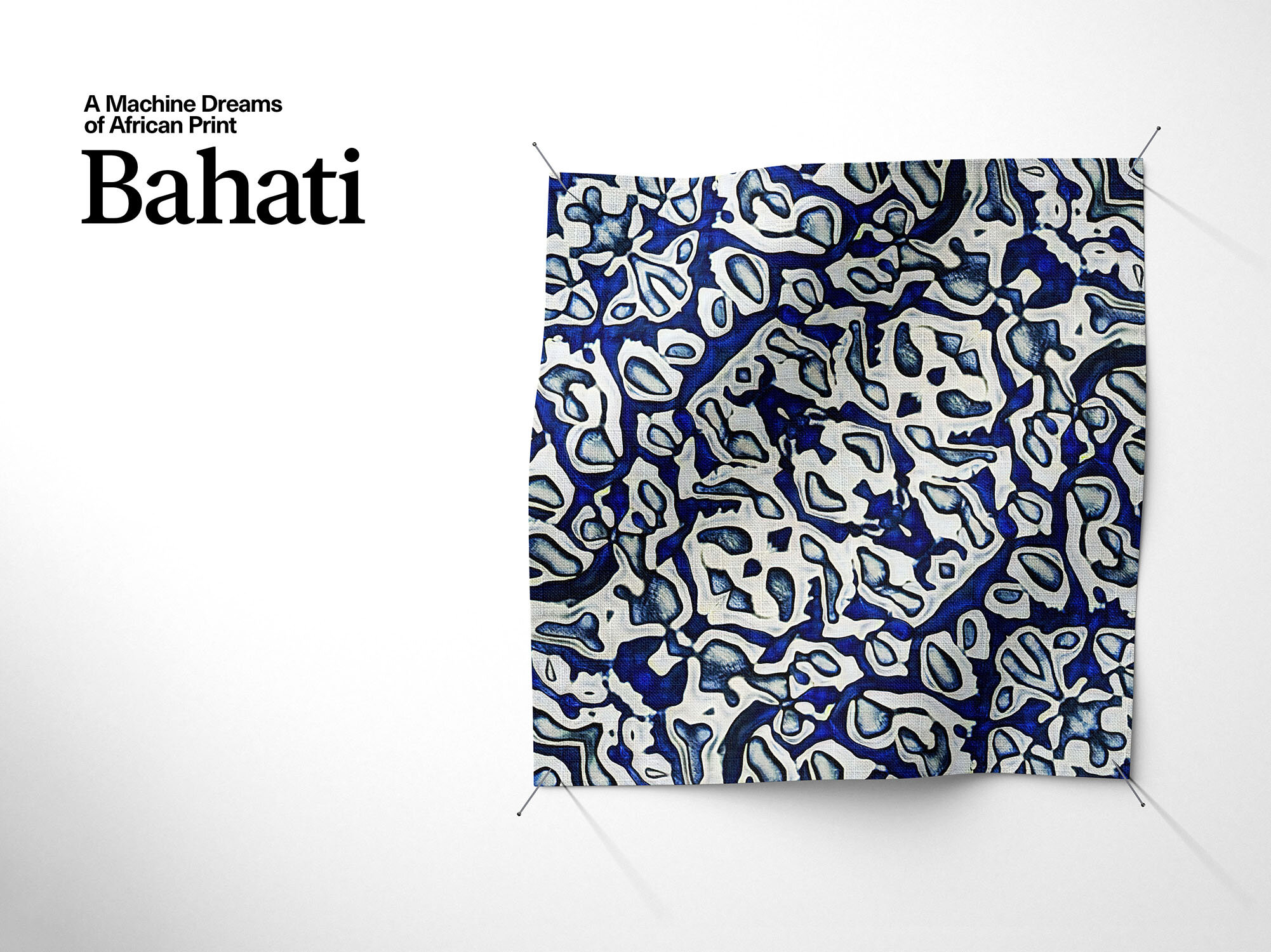

With A Machine Dreams of African Print, Jim Chuchu explores the use of Style Generative Adversarial Networks (StyleGANs for short) to generate new print patterns based on a dataset of prints and motifs from East African fabrics.

Developed as part of the Nest Collective’s Material Languages—a year-long hybrid co-learning with Dutch art centre Stroom den Haag—the project explored the idea of textile and design futures, envisioning a future in which machines take on the labour of creative ideation, a task that was once the preserve and distinctive hallmark of humanity. In theory, this project was also a follow-on to the collective’s virtual-reality short Let This Be A Warning (2017), wherein the collective took the opportunity to adopt and work with emerging creative technologies early in their development.

In this instance, Jim created a large image bank of photographs, scans and drawings of old print and textile works from the region, and fed this as an input to a machine learning model; curious to see what shapes and colours the machine would ‘see’ as possible extrapolations of the whole. A curated selection of the model’s outputs were then digitally processed in readiness for the digital printing process.

We live in a world that exhibits a top-down approach to the dissemination of new technologies, with the ‘top’ being the Global North where most technological innovation arguably happens, and ‘down’ being the Global South—Africa, South Asia and South America—where the populace are imagined to only be consumers of ready-for-market technologies, which then quickly become out of date as new tech is being designed and this cycle begins again. Unless designed specifically for the Global South (i.e. technologies designed to tackle the trinity of Global South problems; disease, poverty and war) emerging creative technologies such as virtual reality, robotics and AI and the promises of 5G and Web 3.0 are often only deployed in the Global South once they are firmly established in the Global North markets. This is a pity, seeing as it is in the Global South where the vast majority of internet and social media users live, and that it is also in these regions where the internet is most rapidly expanding.

In addition, Kenya’s cultural history—that timespan that stretches between Kenya’s pre-existence as a grouping of Bantu kingdoms and the city-states of Azania (‘land of the blacks’), to the formation of the British East Africa Protectorate in 1895, all the way to the anti-colonialism uprisings and subsequent independence in 1964—remains largely frozen in government archives, revisionist educational syllabi and the fading memories of that dwindling number of people who witnessed some part of that history. Perhaps because Kenya—like many other African countries—did not undertake an intensive decolonizing operation, Kenyan society (and its artists and creatives) are implicitly encouraged to view Kenya’s cultural history as a set of rigid narratives that are carefully preserved for the sake of national unity and harmony, a set of incontestable facts about who Kenyans have been in the past and can only be now.

From our beginnings as a collective, we often chose to focus our creative attentions on Kenya’s present and futures in order to steer clear of this baggage that comes with addressing our contested histories. Our later projects, such as our involvement with the International Inventories Programme, have gently pushed us to deploy our lens and praxis upon Kenya’s cultural past, which in turn allow projects such as these—where we allow a very complex machine to process imagery bearing significant sociocultural meaning—to happen. To us, this serves an example of how technology can widen the subjective frame around what is deemed human-ly, blac-kly and African-ly possible.

The resulting prints—named Athi, Bahati, Subra and Tana after the last four rivers that still flow in a Kenya of the distant future—are startlingly ‘hand-crafted’ in their appearance, underscoring the latest iteration of the debate about whether increasingly capable machines can be, indeed, creative in their own right, and—if so—what truly separates man from machine.